I'm playing with technicalities here - I didn't say surfable waves in the title. We can answer this question in a few ways, depending on what "biggest" means to you. Since we're here to learn about surfing, let's stick to waves in the ocean.

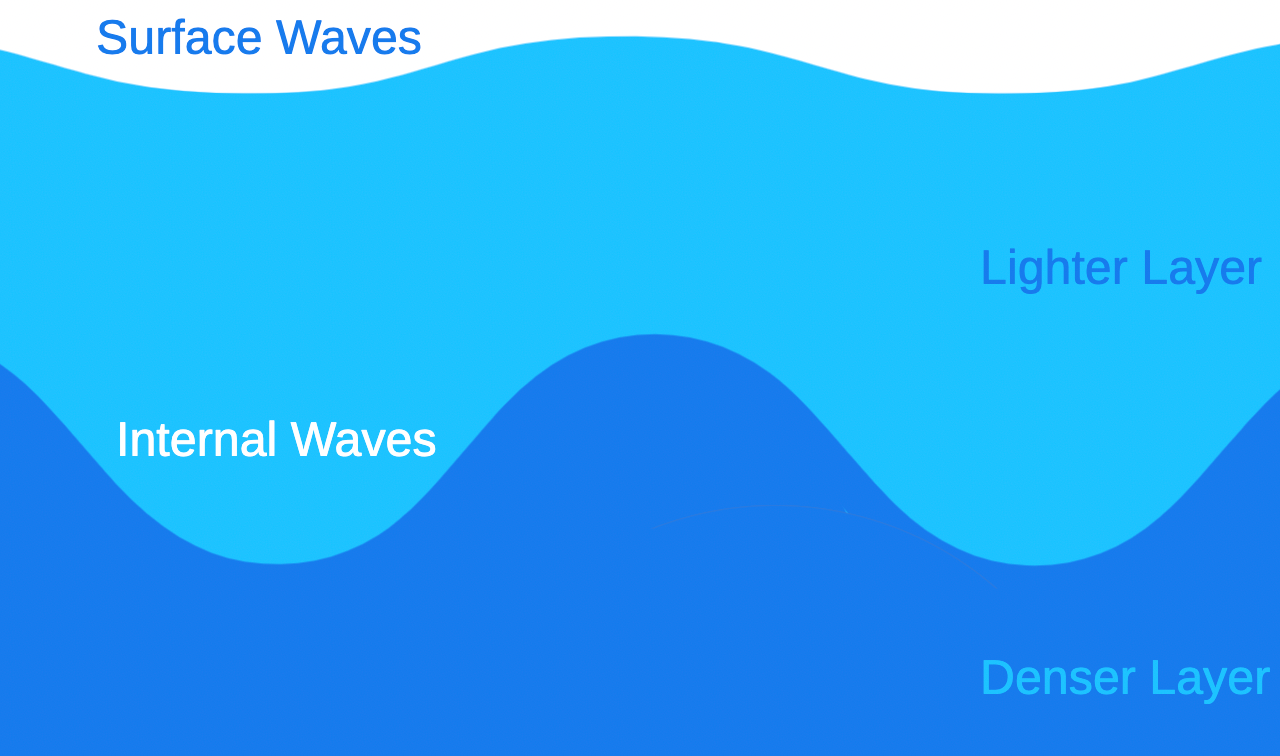

If we're talking tallest waves, we need to look beneath the surface at internal waves - those massive underwater swells that propagate due to stratification in the water column. While there is a wave event that dwarfs even these giants, it's not a regular occurrence.

Internal waves in the South China Sea have been measured with amplitudes around 170m (550ft) tall. That's taller than the Washington Monument. These behemoths form when tidal flows crash over a ridge in the Luzon Strait between Taiwan and the Philippines. Moving westward toward Vietnam and China, they maintain their form as solitons - single waves with pronounced peaks - or trains of these waves.

When these underwater monsters break, still far below the surface, they mix cold, nutrient-rich water onto the continental shelf. This provides both food for marine organisms and a temporary refuge from rising sea temperatures.

Despite being almost entirely underwater, these waves leave surface signatures visible from space, allowing researchers to track them across the basin. Matthew Alford and colleagues documented these waves from generation to disintegration in a paper that is well-referenced in the field.

If we're talking one-off events, nothing tops the 1958 tsunami in Lituya Bay, Alaska. An 8-magnitude earthquake triggered a massive landslide into the bay, creating a tsunami that reached heights over 1700ft on the opposite shoreline. Of the three ships in the bay during this catastrophe, two survived - including one carrying a father and his 7-year-old son, who rode out the wave.

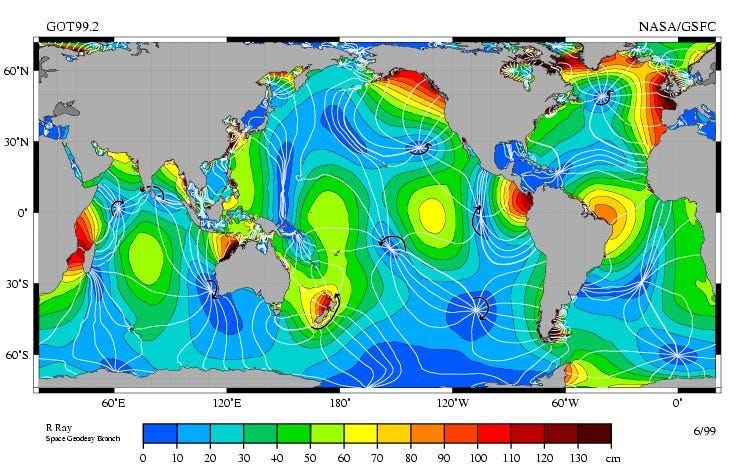

But if we define "largest" by sheer volume, the award goes to the tides. Tides are simply waves driven by the gravitational pull of celestial bodies like the sun, moon, and planets. In a hypothetical world of pure ocean with no land, tides would rotate cleanly around the globe. Our actual coastlines complicate things, creating unique tidal patterns in different ocean basins.

In many of these basins, like the Pacific, the wavelength stretches hundreds to thousands of kilometers. While the height might only be a few meters in many places (your standard tide swing), the sheer volume of water involved dwarfs everything else on the planet due to that huge wavelength.

Now, if we expanded our search to include the atmosphere – which makes sense since gases and liquids are both fluids – we'd need to adjust our perspective. The air above your head sustains internal waves too, and they're vastly larger than their ocean counterparts, with vertical amplitudes measured in kilometers rather than meters.

So while Nazaré, Jaws, or Cortez Bank might come to mind at first, they're wind chop compared to the true giants moving through our oceans and atmosphere.

Further Reading:

Felipe Pomar is reputed to have ridden a tsunami wave.

https://wavelengthmag.com/surfing-through-a-tsunami-in-peru-felipe-pomars-legendary-ride/

I was in Bali in 1977 for the tsunami from the Sumba earthquake and was in the water at Padang Padang when the tide suddenly went out. With my science background I knew what was happening. Others were not so lucky.

https://www.swellnet.com/news/swellnet-dispatch/2014/09/24/tsunami-77