Picture this: It's a sunny August day in San Diego. The beaches are crowded, the sun's been out since 10 am, and you're standing there, wetsuit in hand, wondering if you'll need it. Two days ago, you were sweating while surfing and got a little too much sun. But yesterday? Freezing. So what's the deal with San Diego's ocean temperature playing hot and cold like this?

You'd think that with longer days and hotter air in summer, the water would always be warmer than in winter, right? Well, not quite. In fact, it's possible for a record-breaking heatwave to coincide with water temperatures colder than an average winter day.

Here's the thing: ocean temperatures in San Diego are much more stable day-to-day during winter than in summer. To understand why, we need to talk about something called the thermocline.

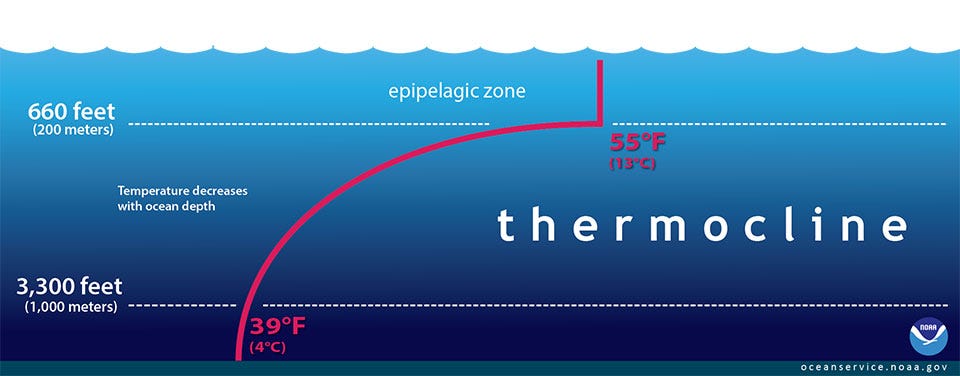

Oceanographers like to think of the ocean in layers from top to bottom. The thermocline is the layer where the temperature changes quickly as you go deeper. This happens because warm water is lighter than cold water, so it floats on top.

In summer, this warm layer is thinner and closer to the surface. Why? Two main reasons:

There are fewer big waves in summer to mix things up.

The sun is out longer, heating up the top layer more.

But if that's the case, why isn't the water always warm in summer? Enter the biggest waves in existence: internal waves.

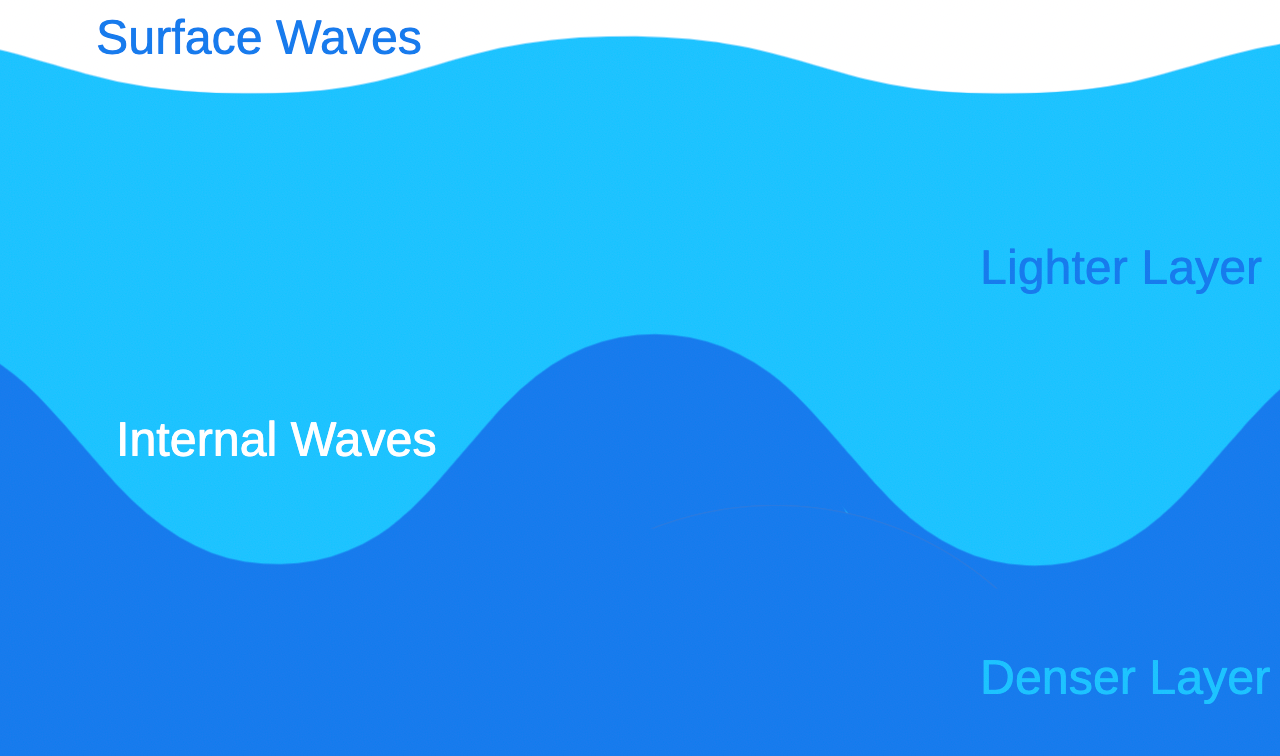

Unlike the waves you see at the beach, internal waves happen underwater, in the “interior” of the ocean. They can be massive, hundreds of feet tall in some regions of the world. These waves can bring cold water from deeper areas up to the shore, suddenly turning your warm session into a chilly dip.

Here's how it works: Something (like currents or wind) pushes lighter water down. But because it's lighter, it wants to float back up. As it does, it overshoots and starts bobbing up and down, creating these underwater waves. When these waves reach shallower areas, they "break" just like surface waves, mixing the cold deep water with the warm surface water.

This mixing can happen pretty slowly relative to the wave you surf - we're talking minutes, hours, or days depending on the type. And they don't break evenly along the coast. Some spots might get hit with cold water while others stay warm, which is why one beach might be freezing while another nearby is perfectly pleasant.

Now, you might be wondering, "Why doesn't this happen in winter?" Well, it does, but the thermocline is much deeper during the cold months. There's more mixing from winter storms, and less heating from the sun which means the thermocline is much deeper. So those internal waves are breaking and mixing water far offshore, where you're not swimming or surfing.

So next time you're at the beach in San Diego and the water suddenly feels like the ocean is personally mocking you for picking trunks, you'll know why. It's just waves that are bigger than the ones you are surfing.

Check out Part II where we'll dive into how wind direction can also change the water temperature in our coastal waters.

Further Reading: